What constitutes a “good” agreement for Indigenous peoples dealing with extractive industries? Why are some agreements so much better than others? And how can outcomes be improved for Indigenous peoples in negotiated agreements?

Dr. Ciaran O’Faircheallaigh has conducted research analyzing over forty agreements between extractives companies and Aboriginal communities in Australia to identify the processes and content that most contribute to successful outcomes for communities. Additional detail on the methodology and scale can be found in the Research Methodology sidebar.

Dr. O’Faircheallaigh’s findings included the following:

- The relative strength of agreements is not dependent on company policy, industry sector, or company size. Strong and weak agreements were found within the same company and within the same sector, and some of the strongest agreements are with medium-sized companies.

- Some agreements can leave Indigenous peoples worse off than having no agreement. For example, while the national law recognizes the legal right of citizens to participate in an environmental legislation process, one Australian agreement prohibits the community from lodging any objections, claims, or appeals to any government authority under any kind of legislation, including environmental legislation – essentially removing their rights as citizens.

- A common misperception is that strengths in some areas of an agreement are likely to reflect tradeoffs in other areas. However, agreements were generally found to be strong across the board of issue sets, or weak across the board. For example, if financial benefits were minimal, environmental provisions were also likely to be poor.

- Legal regime is important but not definitive. For example, under Australia’s Native Title Act (NTA), which governs the majority of Australia, if an agreement is not reached within 6 months, a decision about concession award is made by a government tribunal (which nearly always approve the concession), and the community will not receive any royalty. This de facto lack of a veto, paired with the likelihood of impacts without compensation, means that communities under the NTA face tremendous pressure to sign an agreement before the 6 month timeframe expires. While some strong agreements were still reached in NTA territories, there were also many weak agreements in those areas; in contrast, there were no weak agreements in the Northern Territory, where a community veto is possible under law.

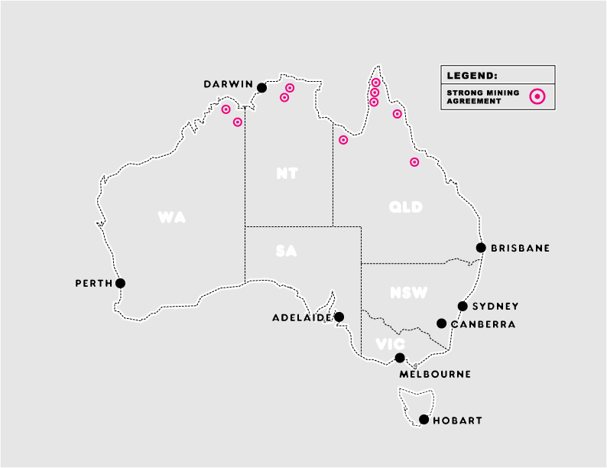

- Community capacity matters; where strong agreements occurred despite unfavorable policy regimes, communities were able to access strong regional political networks with financial and technical resources to support negotiations, make ‘credible threats’ of direct political action, and build on regional legal strategies and precedents for strong agreements. (See graphic.)

- The strongest agreements deliver benefits for industry – highly rated agreements, where industry focuses on good process, capacity building, investments, and complying with cultural heritage legislation, can enhance relationships with and garner support from Aboriginal peoples, reduce environmental risks, and enable compliance with cultural heritage legislation.

- Land councils in Australia draw from deep-seated cultural foundations that have taken thousands of years to evolve. The Kimberley Land Council has a system of cultural and economic exchange that involves all groups in the Kimberley, has been in existence for millennia, and is used in transmission of cultural artifacts and organization of regional ceremonies. Through this platform, the Land Council is able to bring together a region and support local agreement-making through strong capacity building.

Although communities in Western Australia and Queensland fall under the Native Title Act, which essentially eliminates the possibility of a veto, strong agreements were still possible when communities had access to political networks who could offer legal and financial resources, strategies, and precedents to support negotiations.

Research Methodology

The analysis draws from nearly fifty agreements from Australia and Canada, reports on community consultation and negotiation processes, and Dr. O’Faircheallaigh’s direct experiences in leading consultations. A numeric scale of -1 to +6 was developed for each of the following elements of agreements:

- Cultural heritage protection;

- Participation in environmental management;

- Revenue sharing/royalties;

- Aboriginal employment and training;

- Business development opportunities;

- Land use, land access, and recognition of land rights; and

- Agreement implementation.

This scale is not cumulative. Agreements were ranked at the highest point of the scale on which they fall. For example, the area of environmental management was ranked as follows:

- (-1) Provisions that limit existing rights

- (0) No provisions

- (1) Mining company commits to Aboriginal parties to comply with environmental legislation

- (2) Company undertakes to consult with affected Aboriginal people

- (3) Aboriginal parties have a right to access, and independently evaluate, information on environmental systems and issues

- (4) Aboriginal parties may suggest ways of enhancing environmental management systems, and project operator must address their suggestions

- (5) Joint decision-making on some or all environmental management issues

- (6) Aboriginal parties have the capacity to act unilaterally to deal with environmental concerns or problems associated with a project

Dr. O’Faircheallaigh offers some recommendations for building more robust agreements with improved outcomes for communities. These included the following:

- Community controlled impact assessments can help to streamline the eventual negotiation process by building a platform for internal discussions by the community or communities. This process can reveal and begin to resolve tensions within and among communities.

- Although tensions may exist between regional and indigenous communities, strong regional networks can offer strategic capacity and access to expertise that benefits local communities. The development of robust local representative structures should also be prioritized.

- At a broader scale, there is a need to reform the laws, structures, and institutions that undermine indigenous negotiation positions and also tend to result in weak agreements.

Potential further resources include:

- Negotiations in the Indigenous World, 2015. Ciaran O’Faircheallaigh. Dr. O’Faircheallaigh’s research reviews agreement outcomes based on analysis of 45 negotiations between Aboriginal peoples and mining companies across Australia. It also includes detailed case studies of four negotiations in Australia and Canada.